Cambridge, February 26, 2013

Yesterday, Bom Chinburi--one of the students in my

"Bauhaus & the City" studio at RISD--did a wonderful

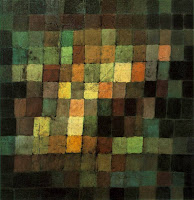

impersonation of Paul Klee, and he mentioned the influence that the French

painter Robert Delaunay had on Klee.

I never thought about this, but Klee explicitly made the connection between his paintings of squares and grids with Delaunay's compositions of circles and arcs.

It made me think of Italo Calvino, when he writes about Turin

and Milan, a comparison that seemed to be quite often in his mind, at least

since 1945 when he chose between the two cities and became an adopted

Turinese. In a 1985 interview

Calvino talks about "... the incompatibility between the grid pattern of one

and the circular plan of the other..." It is as if he believed that the contrasting geometries were

emblematic of the two cities, "... euphoric and extroverted Milan, as

opposed to methodical and cautious Turin..."

But there had to be a twist, of course. Someone like Calvino wouldn't have settled for the

discipline of Turin's grid if he didn't see a bigger payoff, don't you think? In a little note written 25 years

earlier he remarked that "Turin is a city which entices the writer towards

vigour, linearity, style. It encourages

logic, and through logic it opens the way towards madness."

I suspect that Klee would have agreed.

+-+19th+Century+Photograph.jpg)